Joint report on the erosion of the non-refoulement principle in Lebanon since 2018

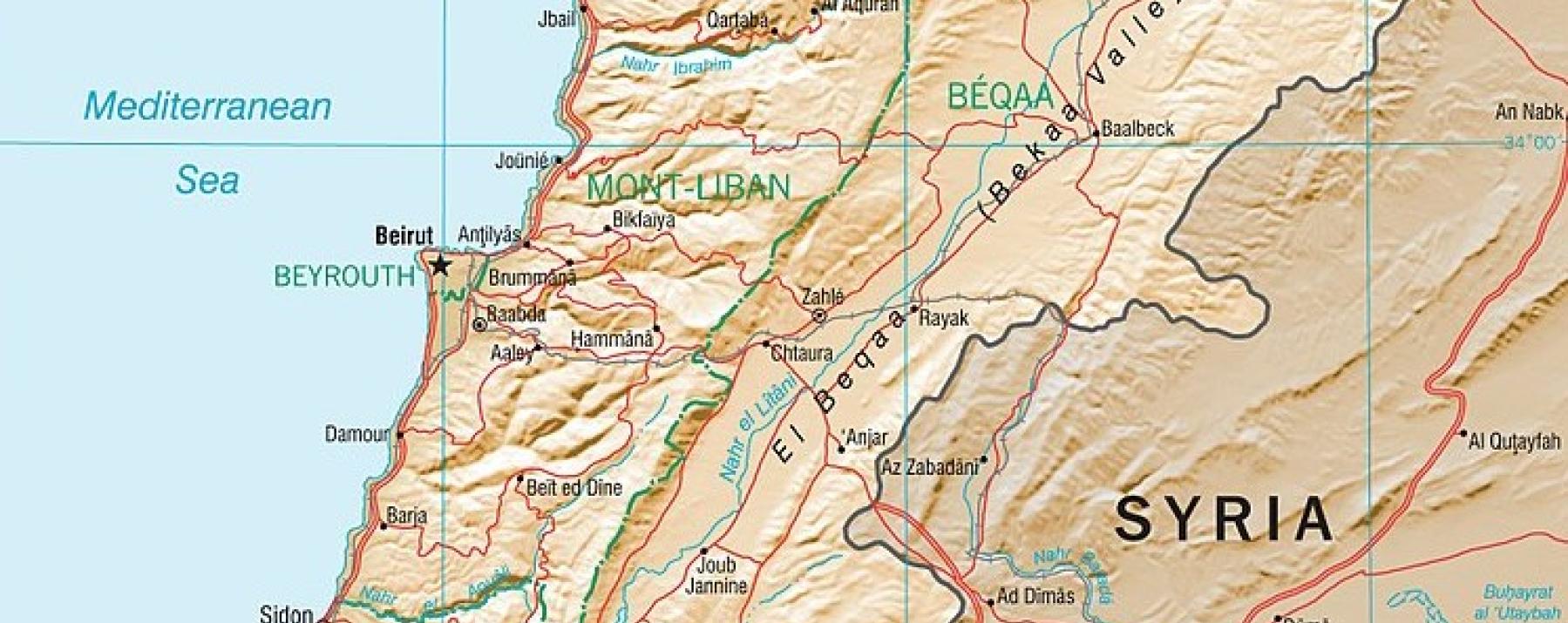

Map from CIA World Factbook 2015.

1. Introduction

The present report analyses Lebanon’s implementation in law and in practice of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), ratified in 1972, in light of the recommendations contained in the Concluding Observations on the third periodic report of Lebanon.[1] Most notably, the Human Rights Committee urged Lebanon to provide, by 6 April 2020, information on the implementation of three recommendations pertaining to violence against women, refugees and asylum seekers and migrant domestic workers. On 15 April 2020, the State party submitted its follow-up report.[2]

The present analysis will mainly focus on Lebanon’s efforts, or lack thereof, to implement the second recommendation, which called on the authorities to:

- Ensure that the non-refoulement principle is strictly adhered to in practice, that all asylum seekers are protected against pushbacks at the border and that they have access to refugee status determination procedures;

- Bring its legislation and practices relating to the detention of asylum seekers and refugees into compliance with article 9 of the Covenant, taking into account the Committee’s general comment No. 35 (particularly para. 18);

- Provide for appeal procedures against decisions regarding detention and deportation;

- Ensure the effective protection of refugees against forced evictions;

- Ensure that curfews, if applied, are imposed only as a short-term and area-specific exceptional measure and are lawful and strictly justified under the Covenant, including under articles 9, 12 and 17;

- Expand the residency fee waiver to include refugees not currently covered.

The present report will mainly address sub-recommendations a, b, c and e, while taking into account information provided by the State party in its follow-up report. The analysis period runs from the issuance of the Committee’s last Concluding Observations on 9 May 2018 and January 2022.

2. Violations of the principle of non-refoulement (article 7)

In its last Concluding Observations, the Committee commended “the State party for its commitment to the principle of non-refoulement and for not enforcing the deportation of Syrian nationals with expired legal status or without legal papers.”[3]

The Committee however expressed concerns at “the strict border admission regulations in place since January 2015, which have resulted in restricted access to asylum and pushbacks at the border with the Syrian Arab Republic that could amount to refoulement, and reports that asylum seekers and refugees originating from countries other than the Syrian Arab Republic are at risk of deportation or refoulement, in particular when there is no prospect of resettlement.”

The Committee also received “[r]eports of the prolonged administrative detention of asylum seekers and refugees other than Syrian nationals, including that of children, without due process, and their expulsion” and highlighted the “broad discretionary powers granted to the General Security Office, pursuant to articles 17 and 18 of the 1962 Act on entry and exit, regarding decisions to detain without judicial warrant and deport individuals from Lebanon, and the lack of appeal procedures relating to such decisions.”[4]

As mentioned in the last Concluding Observations, the registration of Syrian refugees by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Lebanon was suspended by the Government in 2015.[5] In April 2015, the Ministry of Social Affairs even requested that UNHCR de-register over 1’400 Syrian refugees who had arrived in Lebanon after 5 January 2015.[6]

Since the adoption of the Concluding Observations in 2018, the situation has continued to worsen with the authorities taking a number of steps that run contrary to the principle of non-refoulement.

On 15 April 2019, the Higher Defence Council, a government body in charge of national security and headed by the President, adopted several unpublished decisions to stop Syrians from crossing the border irregularly into Lebanon.[7]

On 13 May 2019, the General Director of the General Security issued a decision to summarily deport all Syrians caught crossing the border irregularly after 24 April 2019, and to hand them directly to Syrian government authorities.[8] Prior to this decision, Syrians who were apprehended while attempting to enter Lebanon through unofficial crossing points were pushed back but not handed over to the Syrian authorities.

On 24 May 2019, Human Rights Watch reported on the deportation of 16 Syrian nationals, including at least five registered refugees, from the Hariri International Airport in Beirut.[9]

On the same day, the state-run National News Agency reported that the Lebanese Armed Forces, Internal Security Forces, and General Security had deported a combined 301 Syrians nationals to Syria since 7 May 2019.[10]

Between 13 May and 9 August 2019, according to the General Security and Minister of Presidential Affairs data, 2’447 Syrians had been deported to Syria. It was found that the deportations relied on a notification from the Public Prosecution, without referring them to trial.[11]

In this context, the UNCHR raised its concern over the new policy and practice which – in the absence of legal procedural safeguards – could lead to cases of refoulement.[12]

According to Amnesty International, between mid-2019 and the end of 2020, the General Security deported over 6’000 Syrian refugees, putting them at risk of torture, enforced disappearance, and extrajudicial killings.[13]

On 7 September 2021, Amnesty International issued a report about the violations against Syrian refugees returning to Syria. The report includes 66 cases of individuals who were subjected to severe human rights violations upon their return to Syria, as a direct consequence of perceived affiliation of the affected individuals with the opposition “simply deriving from refugees’ displacement.”[14] The returnees or their relatives stated that the Syrian intelligence officers had subjected women, children and men returning to Syria to violations such as arbitrary detention, torture and other ill-treatment, including sexual violence and rape, as well as enforced disappearance. Based on these findings, Amnesty stressed that no part of the state currently is safe for individuals to return to and that any returnee will be at real risk of persecution, which renders any return to Syria at this time illegal under the non-refoulement obligation.

In October 2021, MENA Rights Group documented the case of Messayar and his brother Mohammed Al Azzawi, two Syrian nationals who have been living in Lebanon since 2017.[15] On 12 June 2019, they were arrested by the Lebanese Military Intelligence. They alleged having been subjected to severe acts of torture by military intelligence officers in order to obtain forced confessions, including that they were fighting with opposition armed groups in Syria. On 11 August 2021, they were both sentenced by the Military Court to three years’ imprisonment. Despite having completed their prison sentence on 30 September 2021,[16] they remained detained at the General Security retention centre in Beirut. On 7 October 2021, Mohammed Al Azzawi was released but his brother Messayar remained in detention. Messayar was then deported to Syria on 22 October 2021. The brothers had fled the protracted conflict in Syria and the compulsory military service. According to the UNHCR, draft evaders in detention face a risk of torture and other forms of ill-treatment.[17]

2.1 The right to seek asylum and the non-refoulement principle under Lebanese law

While Lebanon is not a party to the UN 1951 Refugee Convention, by way of customary international law, the country is bound by the principle of non-refoulement. The country has also ratified the United Nations Convention against Torture (UNCAT), which makes reference to the principle of non-refoulement in its article 3. However, Lebanese law is still deficient regarding the principle of non-refoulement.

The State party acknowledges that there are no national laws specifically covering asylum and claims that “all asylum seekers can benefit from procedures to determine refugee status […] using UNHCR mechanisms and not domestic legislation.” [18]

Such statement is not entirely accurate for two reasons. First, the registration of Syrian refugees by the UNHCR in Lebanon was suspended by the government in 2015, as explained earlier. Second, the 1962 Law Regulating the Entry and Stay of Foreigners in Lebanon and their Exit from the Country contains a number of provisions relating to asylum (1962 Law of Entry and Exit).

Its article 26 states that “[e]very foreigner who is persecuted or sentenced for a political crime outside Lebanon, or whose life or liberty is threatened on account of political activity, may apply for asylum in Lebanon.” Under the 1962 Law of Entry and Exit, the right to political asylum is granted only by a commission composed of the Minister of Interior, the Directors of the Ministry of Justice, Social Affairs, and General Security. In practice, there is currently no operational asylum procedure in Lebanon.

Article 31 of the Law of Entry and Exit also provides for the non-refoulement of a former political refugee.

Finally, we regret that Law No. 65 on the Punishment of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment does not contain a specific provision reflecting article 3 UNCAT.

Recommendations:

- Implement recommendation 38(a) from the Human Rights Committee’s Concluding Observations of 2018, which provides that the State Party should “[e]nsure that the non-refoulement principle is strictly adhered to in practice, that all asylum seekers are protected against pushbacks at the border and that they have access to refugee status determination procedures”;

- Include explicit non-refoulement provisions in Law No. 65 on the Punishment of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and in the Code of Criminal Procedure;

- Ratify the UN 1951 Refugee Convention;

- Until a national asylum procedure is in place, allow the UNHCR to resume the registration and asylum determinations of Syrian nationals in need of protection;

- Provide procedures that enable asylum seekers to appeal decisions regarding their deportation.

3. The detention of asylum seekers and refugees in law and practice (article 9)

We regret that the State party failed to provide information regarding the implementation of the second sub-recommendation, which calls on the State party to bring its legislation and practices relating to the detention of asylum seekers and refugees into compliance with article 9 of the Covenant, taking into account the Committee’s General Comment No. 35.[19]

Article 8 of the Lebanese Constitution provides that “no one may be arrested, imprisoned, or kept in custody except according to the provisions of the Law. No offense may be established or penalty imposed except by Law”. Any deprivation of liberty without legal justification or without the sanction of an appropriate legal authority can therefore be considered arbitrary.

Under Article 367 of the Penal Code, any official who arrests or imprisons an individual in cases other than those provided for by law can be sentenced to forced labour for life. Under the following article, officials who have held an individual without a warrant or court decision or have detained a person beyond the statutory time limit can be sentenced to three years in prison. In practice, the aforementioned safeguards and obligations are frequently breached with regard to non-citizens.

According to the Global Detention Project, although Lebanese law provides rudimentary grounds for the administrative detention of non-citizens, observers in and outside Lebanon have long noted that the legal framework is unclear and inadequate, often resulting in arbitrary and indefinite detention.[20]

3.1 Administrative detention

The only specific ground provided in law that can lead to the administrative detention of a non-citizen is a threat to national security or public safety. According to article 17 of the Law of Entry and Exit, a removal order can be issued to a non-citizen on the grounds that his or her continued presence is a threat to general safety and security.

The Director of General Security is subsequently authorised to detain the individual with approval of the Public Prosecutor until their deportation under article 18. However, in addition to requiring the public prosecutor’s consent, the Ministry of Interior must also be informed of all expulsion orders (article 17).[21] There is no established maximum time limit to administrative detention.

There have been cases where migrants have been detained for years according to the Lebanese Centre for Human Rights and ALEF.[22] Yet, following Court ruling No. 261/2015, Judge Jad Maalouf found that administrative detention should be a measure of exception and not the norm.[23]

3.2 Criminal sanctions

Lebanese law provides specific criminal penalties for immigration-status-related violations. Foreign nationals who are charged with criminal violations stemming from their status can face three distinct stages of incarceration: pre-trial detention, criminal incarceration upon conviction, and detention while awaiting removal from the country after the completion of a prison sentence.

Foreigners can receive prison sentences for the following immigration-related infringements of the Law of Entry and Exit: irregular entry, use of forged identity papers and concealment of identity; remaining in the country following the rejection of a new residence permit and re-entry or exit via unauthorised posts, continued stay in the country after the issuance of a deportation order on security grounds, irregular re-entry, and non-timely extension of a residence permit.

Under article 32 of the 1962 Law of Entry and Exit, non-citizens who are convicted of entering Lebanon without proper authorisation or using false identities can be sentenced to up to three months in prison, fined, and served an expulsion order. Article 33 states that non-citizens who do not leave the country after a new residency permit is refused, or who attempt to re-enter or exit Lebanon through an unauthorised entry point, can be taken into custody and charged with crimes leading to criminal incarceration and fines. According to article 34, an individual who fails to adhere to an expulsion order issued on security grounds can face up to six months imprisonment, while article 35 also provides for up to six months imprisonment for illegal re-entry following expulsion. A delayed application to extend a residence permit can also result in imprisonment for one week to two months under article 36.

If non-citizens violate provisions of the 1962 Law of Entry and Exit, they can face deportation. According to article 89 of the Lebanese Criminal Code, the concerned person should be released after the completion of their sentences in order to “leave Lebanese territory by his own means within 15 days”. It further states that the “breach of a judicial or administrative deportation measure shall be punishable by imprisonment for a term of between one and six months.”

However, in practice foreigners are usually kept in detention after having completed their sentences.[24] Following the completion of criminal sentences, non-citizens can be handed over to the General Security. Such practice is facilitated by internal administrative directives and directives of the Public Prosecutor that appear to provide for a form of administrative detention of non-citizens.[25]

3.3 Difficulties to comply with 1962 Law of Entry and Exit

It has becoming increasingly difficult for Syrian refugees to enter Lebanon through regular channels. Admission to Lebanon is currently restricted to those who can provide valid identity documents and proof that their stay in Lebanon fits into one of the approved reasons for entry. Seeking refuge is not among the valid reasons for entry, other than in exceptional circumstances approved by the Ministry of Social Affairs.[26]

In addition, many have faced growing difficulties to obtain or renew their residency permit in the country despite the adoption of the fee waiver policy in 2017. According to the UNHCR, the percentage of Syrian refugees holding valid legal residency has further decreased, as the number of refugees able to pay for residency renewal has reduced and fewer fall within the criteria of the 2017 fee waiver. According to the Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon, less than 50 percent of Syrian refugees can benefit from the waiver.[27]

Already in 2018, the Committee raised concerns at the limited coverage of the residency fee waiver policy.[28] A lack of legal residency expose Syrian refugee to the risk of arrest and detention under the terms of the 1962 Law of Entry and Exit as detailed in the present section.

In 2020, rates of legal residency continued to decline, with only 20% of individuals above the age of 15 holding legal residency permits (compared to 22% in 2019 and 27% in 2018). This is mainly due to rejections by General Security Office, including inconsistent practices, the inability to obtain a sponsor or pay the residency fees (not eligible to the waiver) and the limitation of the existing regulations.[29]

According to the UNHCR, non-Syrian refugees without legal residency are particularly vulnerable and at high risk of deportation to their country of origin.[30]

3.4 Treatment of Syrian nationals in detention

In late 2021, MENA Rights Group has documented several cases of Syrian nationals who have been detained while awaiting deportation from Lebanon.

In late August 2021, six Syrian nationals were arrested near the Syrian embassy in Baabda where they were to be issued passports.[31] The army detained them for “entering the country illegally” before the Lebanese General Security took over their cases. They were detained incommunicado until 1 September 2021, when they were finally able to meet their lawyers at the detention centre of the General Security in Beirut. While detained incommunicado, they were subjected to torture and ill-treatment.

On 2 September 2021, one of the complainants’ lawyers submitted a complaint before the Public Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation invoking a violation of Law No. 105 for the Missing and Forcibly Disappeared,[32] article 47 (1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP), and article 37 of the Penal Code, in reference to the abduction and incommunicado detention of the complainants. The complaint also invoked a violation of Law No. 65/2017 on Punishment of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and made a reference to article 32 of the CCP.[33] The complaint further invoked a possible violation of article 3 of the Convention against Torture should the complainants be deported to their country of origin. The lawyer called for an investigation into the allegations made by the complainants, a medical examination by a forensic doctor of the complainants, the prosecution of anyone found in breach of the aforementioned provisions and demanded that his clients are not handed over to the Syrian authorities. The complaint was not followed through by the prosecutor. Although they initially faced imminent deportation to Syria, Major General Abbas Ibrahim, the head of Lebanon’s General Security, ordered their release on 9 September. They remained detained in an immigration detention centre until 12 October 2021, when they were finally released.

Recommendations:

- Take steps to bring migration-related law and policy into conformity with the recommendations provided in the Committee’s General Comment No. 35 concerning “Liberty and security of person”;[34]

- Ratify the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families;

- Ensure that children must never be detained for reasons related to their immigration status in light of Joint General Comments No. 4 and No. 23 regarding the human rights of children in the context of international migration in countries of origin, transit, destination and return;[35]

- Investigate all allegations of torture and ill-treatment committed in detention in compliance with Law No. 65/2017 on Punishment of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment regardless of the legal status of the complainant;

- Ensure unrestricted access to immigration detention centres to the newly established National Preventative Mechanism against Torture (NPM);

- Refrain from detaining non-nationals in breach of the 1962 Law of Entry and Exit;

- Allow refugees to maintain legal status by expanding the residency fee waiver to all Syrians in Lebanon;

- Lift restrictive visa regulations leaving most refugees from neighbouring countries unable to enter Lebanon regularly;

- Adopt and implement maximum time limits on immigration detention to avoid arbitrary, prolonged, and/ or indefinite detention of non-citizens.

The State party claims that “[u]nder applicable Lebanese laws and regulations, all administrative decisions are subject to review at the request of the party concerned.”[36] In the present section, we will demonstrate that the review processes are neither available nor effective in law and practice for non-nationals deprived of liberty in immigration detention centres.

As with all administrative decisions, a General Security decision can be challenged before an administrative judge within two months of the detainee being notified.[37] According to a study conducted by the Global Detention Project, there were no known cases where a non-citizen was able to challenge the legality of his or her detention before an administrative judge in 2018.[38]

General Security detention decisions regarding refugees and asylum seekers can be challenged before the Minister of Interior. In addition, the Lebanese Conseil d’Etat has acknowledged that it has the power to interfere with General Security’s discretionary power to issue a deportation order. This power is limited to ensuring that the decision is not legally flawed.[39] In practice, however, the judicial authorities rarely scrutinise or review the legalities of detention.[40]

Article 579 of the Code of Civil Procedures grants the Judge of urgent matters[41] the ability to put an end to the administration’s infringement on personal rights. The urgent matter judge can be seized for example in case the deadlines set out at article 47 of the Code of Criminal Procedures are not respected — article 47 states that detention prior to a hearing before a magistrate should not exceed 48 hours and can only be renewed once — or when a foreign national is detained after the expiration of his or her sentence.

Rights groups have claimed that police do not always respect these limits and that in reality, migrants are often detained for an average initial period of 16 days.[42] Mohamed Sablouh, a human rights lawyer who represents Syrian nationals at risk of deportation, told MENA Rights Group that some of his clients have been detained in detention centres run by the General Security for periods exceeding 50 days. For those cases, Mohamed Sablouh filed an emergency injunction before the judge of urgent matters, but the judge has yet to rule on the arbitrary character of their detention. According to him, the decisions of urgent matter judges are not necessarily implemented.

A person subjected to a deportation order can also appeal before the urgent matter judges. According to the International Commission of Jurists, “there were cases where deportation was prevented by an urgent matters judge, but only for a limited period of time, which did not necessarily mean that the refugee concerned was no longer under threat of deportation, as he or she might still be arrested again and eventually deported.”[43]

Recommendations:

Take legislative, administrative, judicial and other preventive measures, including:

- Ensuring the right of each person concerned to have his/her case examined individually and not collectively, to be fully informed of the reasons why he/she is the subject of a procedure which may lead to a decision of deportation, and of the rights legally available to appeal such decision;

- Providing access of the person concerned to a lawyer, to free legal aid when necessary, and access to representatives of relevant international organizations of protection;

- The right of appeal by the person concerned against a deportation order to an independent administrative and/or judicial body within a reasonable period of time from the notification of that order and with the suspensive effect of its enforcement.

5. Discriminatory curfews and restrictions of movement

The last Concluding Observations refer to “reports of evictions, curfews and raids targeting in particular Syrian refugees”.[44]

Lebanese towns continued to rely on Decree-law No. 118 (the Municipal Act). Its article 74 provides that the management of circulation and protection of public safety and security are under the jurisdiction of local authorities and more specifically municipalities.

However, according to Legal Agenda, “the Municipal Act does not explicitly state in any of its articles the right of the municipal council or its president to impose a curfew, as the tasks of the aforementioned entities are entrusted with maintaining comfort, safety and public health, provided that it does not conflict with the powers granted by laws and regulations to the security departments in the state.” Legal Agenda recalled that only the military authorities have the power to impose a curfew on people and cars according to a decision and conditions set by the emergency law.[45]

The practice of discriminatory curfews targeting non-nationals or Syrian nationals continued after 2018. In July 2021, the Municipalities of Mari and Majidieh issued a circular forbidding non-Lebanese nationals to roam after 8 pm invoking an increase in the number of burglaries.[46]

While municipalities initially invoked security concerns as a justification for imposing curfews on Syrian citizens, notably in the context of the Syrian civil war and its consequences in Lebanon, the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic provided an additional justification for restricting the freedom of movement of Syrian citizens.

During the pandemic, it has been reported that “at least 21 Lebanese municipalities introduced restrictions on Syrian refugees that do not apply to Lebanese citizens. In some areas, bans on movement and gathering were imposed on Syrians before they were extended to Lebanese. As informal refugee settlements were put under curfews, more security personnel were deployed to these areas to police the daily lives of refugees.”[47]

In February 2020, Al Khader municipality prevented Syrians from roaming from 6 pm until 6 am.[48]

Similarly, on 16 March 2020, the municipality of Bsharri issued Administrative Decision No. 7 aimed at preventing the roaming of displaced Syrians inside the town except for the most utmost necessities related to securing food, drink and hospitalisation. The municipal police was tasked to enforce the decision.[49] The decision blamed the 994 displaced Syrians living in Bsharri for their “lack of commitment to prevent the spread of the Coronavirus.”

Recommendation:

- Ensure in law and in practice that curfews are not applied in a discriminatory manner and comply with Article 2 (1) ICCPR.

6. About the authors

MENA Rights Group is a Geneva-based legal advocacy NGO defending and promoting fundamental rights and freedoms in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Adopting a holistic approach, we work at both the individual and structural level. We represent victims of human rights violations before international law mechanisms. In order to ensure the non-repetition of these violations, we identify patterns and root causes of violations on the ground and bring key issues to the attention of relevant stakeholders to call for legal and policy reform.

The Global Detention Project (GDP) is a non-profit organisation based in Geneva that promotes the human rights of people who have been detained for reasons related to their non-citizen status. Our mission is:

- To promote the human rights of detained migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers;

- To ensure transparency in the treatment of immigration detainees;

- To reinforce advocacy aimed at reforming detention systems;

- To nurture policy-relevant scholarship on the causes and consequences of migration control policies.

[1] Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations on the third periodic report of Lebanon, 9 May 2018, CCPR/C/LBN/CO/3 (hereinafter: 2018 Concluding Observations).

[2] Human Rights Committee, Follow-up report regarding the implementation by Lebanon of the recommendations made by the Human Rights Committee following its consideration, in 2018, of the country’s third periodic report regarding the fulfilment of obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, submitted on 6 April 2020, CCPR/C/LBN/FCO/3 (hereinafter: Lebanon’s follow-up report).

[3] 2018 Concluding Observations, op. cit., para. 37.

[4] Ibidem.

[5] UNCHR, Lebanon/protection, https://www.unhcr.org/lb/protection (accessed 6 January 2022).

[6] Inter-agency Coordination Lebanon, Protection Monthly Dashboard, April 2015, available at:

https://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/working_group.php?Page=Country&LocationId=122&Id=25 (accessed 20 January 2022).

[7] Human Rights Watch, Lebanon: Syrian Refugee Shelters Demolished, 5 July 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/05/lebanon-syrian-refugee-shelters-demolished (accessed 6 January 2022).

[8] General Director of the General Security Decision No. 43830/ق.م.ع of 13 May 2019.

[9] Human Rights Watch, Lebanon: Syrian Refugee Shelters Demolished, 5 July 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/05/lebanon-syrian-refugee-shelters-demolished (accessed 6 January 2022).

[10] Ibidem.

[11] Legal Agenda, 29 May 2019, https://legal-agenda.com/%d9%85%d8%ac%d9%84%d8%b3-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%af%d9%81%d8%a7%d8%b9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a3%d8%b9%d9%84%d9%89-%d9%8a%d9%88%d8%b1%d8%b7-%d9%84%d8%a8%d9%86%d8%a7%d9%86-%d9%81%d9%8a-%d8%aa%d8%b1%d8%ad%d9%8a%d9%84/ (accessed 6 January 2022).

[12] UNHCR, Operational update, April-June 2019, https://www.unhcr.org/lb/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2020/07/Q2-2019-operational-update.pdf (accessed 6 January 2022).

[13] Amnesty International, Urgent appeal: rights organizations call on Lebanese authorities to cease the intimidation of human rights lawyer Mohammed Sablouh, 13 October 2021, https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/MDE1848732021ENGLISH.pdf (accessed 6 January 2022).

[14] Amnesty International, “You’re going to your death” – Violations against Syrian refugees returning to Syria, 7 September 2021, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/amnesty-youregoingtoyourdeath.pdf (accessed 6 January 2022), p. 5.

[15] MENA Rights Group, Syrian national Messayar Al Azzawi deported from Lebanon to Syria, while his brother is released, 4 October 2021, https://www.menarights.org/en/case/messayar-and-mohammed-al-azzawi (accessed 11 January 2022).

[16] In Lebanon, a year in prison amounts to nine months.

[17] UNHCR, Relevant Country of Origin Information to Assist with the Application of UNHCR’s Country Guidance on Syria, 7 May 2020, https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5ec4fcff4.pdf (accessed 6 January 2022), pp. 9-10.

[18] Lebanon’s follow-up report, op. cit., para. 48.

[19] Lebanon’s follow-up report, op. cit., see sub-recommendation b).

[20] Global Detention Project, Immigration detention in Lebanon: deprivation of liberty at the frontiers of global conflict, February 2018, (hereinafter: Immigration detention in Lebanon); https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/GDP-Immigration-Detention-Report-Lebanon-2018-1.pdf (accessed 10 January 2022), pp. 6-7.

[21] ALEF et al., Lebanon Joint Shadow Report, 20 March 2017, http://www.khiamcenter.org/images/UserFiles/Image/NGO%20coalition_CAT_LEB_ShadowReport_Final_20170320_EN(1).pdf (accessed 20 January 2022).

[22] Immigration detention in Lebanon, op. cit., p. 7.

[23] Joint Report submitted to the Committee against Torture in the context of the initial review of Lebanon, 20 March 2017, https://www.khiamcenter.org//images/UserFiles/Image/NGO%20coalition_CAT_LEB_ShadowReport_Final_20170320_EN(1).pdf (accessed 20 January 2022).

[24] Immigration detention in Lebanon, op. cit., p. 8.

[25] Immigration detention in Lebanon, op. cit., pp. 10-11.

[26] UNHCR, Lebanon, https://www.unhcr.org/lb/protection, (accessed 7 January 2022).

[27] The VASyR 2018 report is available at: http://ialebanon.unhcr.org/vasyr/files/previous_vasyr_reports/vasyr-2018.pdf (accessed 7 January 2022).

[28] 2018 Concluding Observations, op. cit., para. 37.

[29] For more information, see VASyR 2020 report available at: http://ialebanon.unhcr.org/vasyr/#/ (accessed 7 January 2022).

[30] UNHCR, Lebanon, Fact Sheet, May 2021, https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/Lebanon%20operational%20fact%20sheet-May%202021.pdf (accessed 7 January 2022).

[31] MENA Rights Group, Six Syrian nationals at risk of deportation from Lebanon to Syria, 11 October 2021, http://www.menarights.org/en/case/tawfiq-al-hajji-ammar-qazzah-mohammed-al-waked-mohammed-abdulelah-ibrahim-al-shammari-and (accessed 7 January 2022).

[32] The complaint makes reference to article 37 of Law No. 105, which states that “[e]ach individual who is an instigator, actor, partner or intervener in the crime of enforced disappearance is to be punished with hard labor from 5 to 15 years and is to be fined between 15 million to 20 million LBP.”

[33] Article 32 of the CCP states that “whoever has any information about a crime that allows taking action without an allegation, should notify the Public Prosecution or any of the investigation officers about it.”

[34] In relation to detention in the course of proceedings for the control of immigration, the Committee recommends in its General comment No. 35 that “detention must be justified as reasonable, necessary and proportionate in the light of the circumstances and reassessed as it extends in time. Asylum seekers who unlawfully enter a State party’s territory may be detained for a brief initial period in order to document their entry, record their claims and determine their identity if it is in doubt. To detain them further while their claims are being resolved would be arbitrary in the absence of particular reasons specific to the individual, such as an individualized likelihood of absconding, a danger of crimes against others or a risk of acts against national security. The decision must consider relevant factors case by case and not be based on a mandatory rule for a broad category; must take into account less invasive means of achieving the same ends, such as reporting obligations, sureties or other conditions to prevent absconding; and must be subject to periodic re-evaluation and judicial review. Decisions regarding the detention of migrants must also take into account the effect of the detention on their physical or mental health. Any necessary detention should take place in appropriate, sanitary, non-punitive facilities and should not take place in prisons. The inability of a State party to carry out the expulsion of an individual because of statelessness or other obstacles does not justify indefinite detention. Children should not be deprived of liberty, except as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time, taking into account their best interests as a primary consideration with regard to the duration and conditions of detention, and also taking into account the extreme vulnerability and need for care of unaccompanied minors.”

[35] UN Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (CMW), Joint general comment No. 4 (2017) of the Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families and No. 23 (2017) of the Committee on the Rights of the Child on State obligations regarding the human rights of children in the context of international migration in countries of origin, transit, destination and return, 16 November 2017, UN Doc. CMW/C/GC/4-CRC/C/GC/23.

[36] Lebanon’s follow-up report, op. cit., para. 50.

[37] Article 2 of Decision 2979 of 9/2/1925 organisation of the Conseil d’Etat.

[38] Immigration detention in Lebanon, op. cit., p. 14.

[39] Conseil d’Etat, Decisions No.235 of 17 May 1971, Case No. 189/69 Felicite Rifa vs State.

[40] Immigration detention in Lebanon, op. cit., p. 14.

[41] Juge des référés (in French).

[42] Immigration detention in Lebanon, op. cit., p. 13.

[43] International Commission of Jurists, Unrecognized and Unprotected, November 2020, https://www.icj.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Lebanon-Migrant-rights-Publications-Reports-Thematic-reports-2020-ENG.pdf (accessed 11 January 2022).

[44] 2018 Concluding Observations, op. cit., para. 37 d).

[45] Legal Agenda, قرارات حظر التجول ضد الأجانب وضد المواطنين السوريين غير قانونية, 14 July 2016, https://legal-agenda.com/%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%AD%D8%B8%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%AC%D9%88%D9%84-%D8%B6%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%AC%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%A8-%D9%88%D8%B6%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%88%D8%A7/ (accessed 6 January 2022).

[46] Elnashra, بلدية الماري والمجيدية: يمنع التجول بعد الساعة الثامنة ليلاً للجنسيات غير اللبنانية , 23 July 2021, https://www.elnashra.com/news/show/1518014/%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%8A-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%8A%D9%85%D9%86%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%AC%D9%88%D9%84-%D8%A8%D8%B9%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AB%D8%A7 (accessed 6 January 2022).

[47] Refik Hodzic, Plight of Syrian refugees in Lebanon must not be ignored, 26 January 2021, Al Jazeera, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/1/26/plight-of-syrian-refugees-in-lebanon-must-not-be-ignored (accessed 19 January 2022).

[48] LBC International, بلدية الخضر تمنع تجول السوريين من الـ6 مساء حتى الـ6 صباحا , 19 February 2020, https://www.lbcgroup.tv/news/d/lebanon/502279/%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%D8%B6%D8%B1-%D8%AA%D9%85%D9%86%D8%B9-%D8%AA%D8%AC%D9%88%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%8A%D9%86-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%806-%D9%85%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D8%AD%D8%AA%D9%89-%D8%A7%D9%84/ar (accessed 6 January 2022).

[49] Administrative decision No. 7 is available on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/BsharriMunicipality/photos/%D8%B9%D8%B7%D9%81%D8%A7-%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%82%D8%A9-%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%8A-%D8%AC%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%AF-%D8%A8%D9%85%D9%86%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%AC%D9%88%D9%84-%D9%84%D9%84%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%B2%D8%AD%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%AE%D9%84-%D8%A8%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%8A/2911154518927530/ (accessed 6 January 2022).